In the grip of the past

Notes on the lives of images

Rasha Dakkak

|

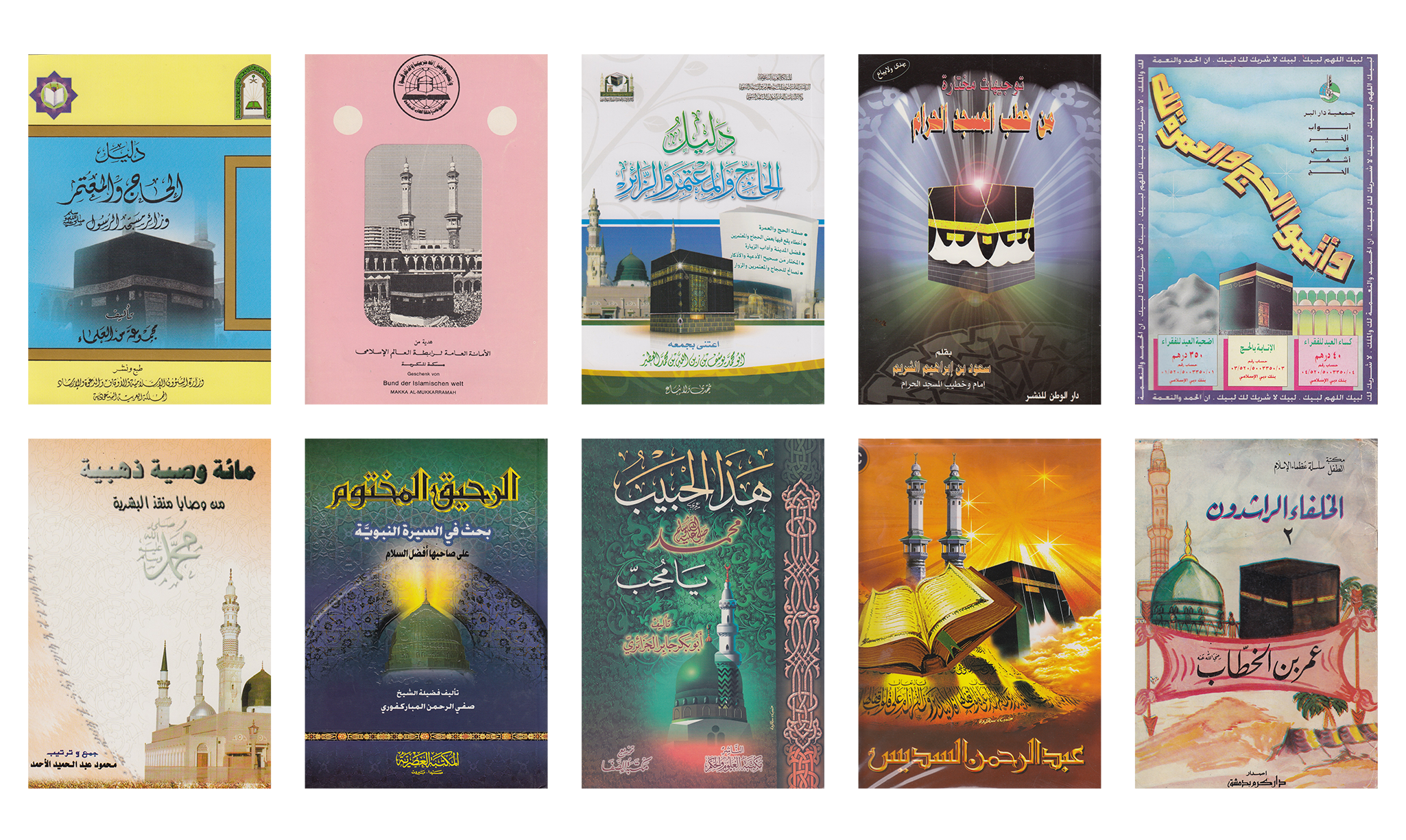

Commonly, images act as agents, engaging the human body and motivating, seducing or sometimes alarming it. Their power includes the ability to make physically present what is otherwise distant or absent. Images can link the embodied presence (the here) with the virtual (there). Thus, as religious practices are known for their lack of reliance on physical space, images have long been used in this context to ignite associations, transforming secular spaces or moments into sacred ones. Note how many religious material cultures incorporate imagery for locations, such as the Kaaba in Mecca or the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, or mosques in general, on prayer mats. As per my findings, the representation of these spaces is used as a mnemonic aid to assist in recalling specific ideas, emotions and memories. But do they still uphold this mandate?

|

|

Maintaining consistency or adhering to a particular aesthetic has its benefits. However, the reproduction of visuals, combined with an excess of reverence for what has been bestowed throughout the generations, has over time turned inheritance into lifeless conventions.

Perhaps if we start distinguishing between tradition and traditionalism, we can eliminate a fundamental confusion that cultures face when it comes to the veneration of inheritance. Tradition is being informed with an accumulated experience and using it as a foundation for growth, as opposed to traditionalism, which is extreme respect for legacy that could impose limitations, prohibit diverse interpretations and eventually becomes a cemetery for evolvement.

These phenomena are about how we perceive what we inherit and how we react to it, and they are not limited to a single practice.

My journey of inquiry into this topic began in 2015 when I started to consider prayer mats. I sought to understand this object’s process of development and the formation of its aesthetics. In my first study, I documented prayer mats of various designs, colours, sizes, and manufacturing origins and recognised that 77% of them included a prayer niche icon. Further, I realized that, aside from cleanliness and purity, the most distinguishing feature of the prayer mat is that it is unidirectional rather than symmetrical, with a clear top and bottom. The practitioner stands at the bottom and the top points in the direction of Mecca. In noticing this, I wondered what other elements we could introduce to provide directionality? This insight offers endless possibilities and prompted me to consider religious material culture beyond prayer mats. As such, I broadened my research to include other artefacts to comprehend their visual language.

If you type the word "Islam" into a search engine, you will get a jumble of images of mosques, the Kaaba, hands raised praising, light source, Quran (sometimes floating), Mihrab, or prayer niche, prayer mats, crescents, and so on.

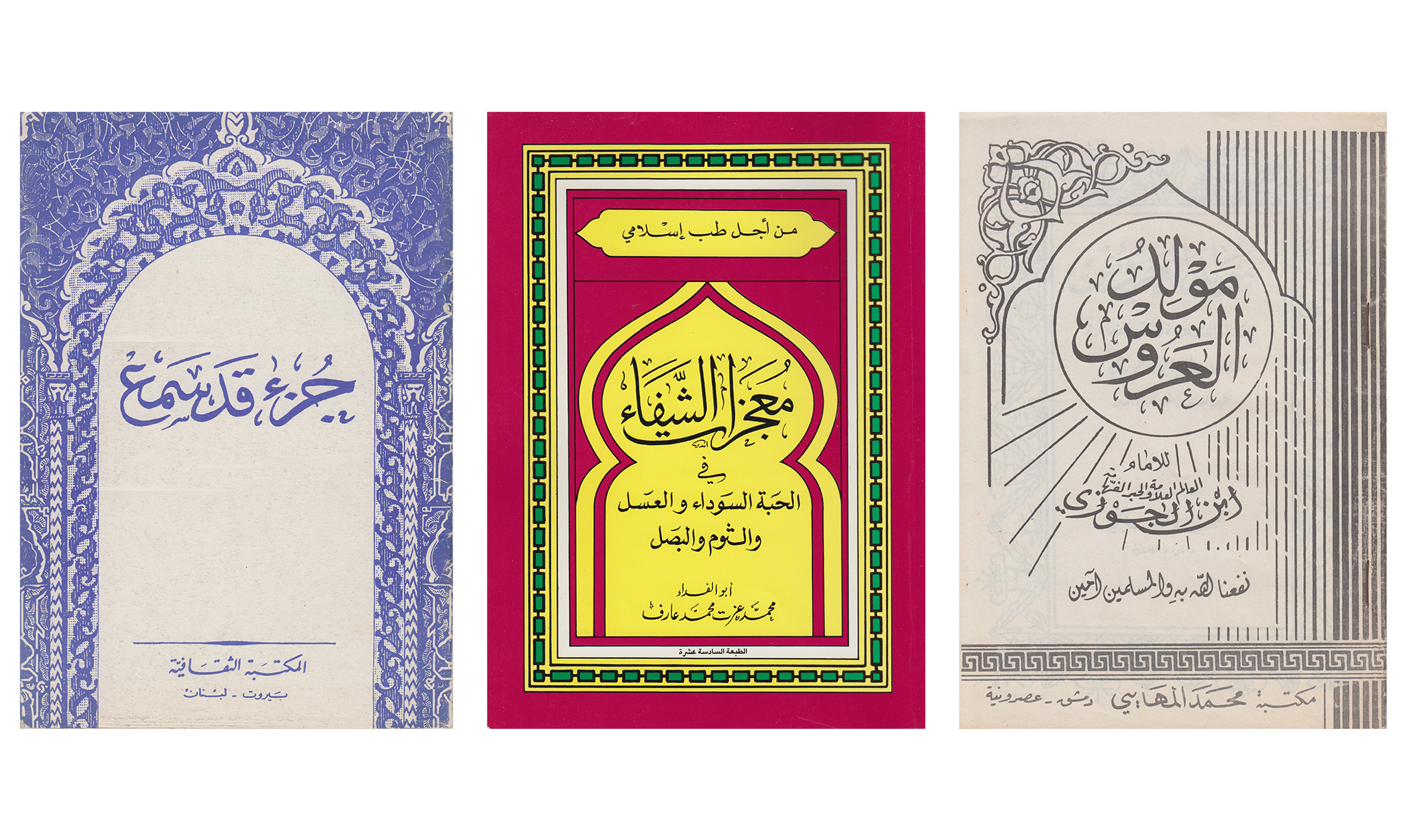

Take, for example, the Mihrab or prayer niche, which is a semi-circular niche in a mosque's wall. This architectural element is a recurring icon and was once viewed as a metaphor symbolising a transition from the earthly to the celestial world.

This form is prevalent in various architectural traditions: the apse of churches, the ark of synagogues, and the throne niche of palaces—among others—are all possible origins of the Mihrab. When deposited within the Islamic architectural and cultural context, the form acquired new functions. During the reign of the Ummayyad caliph Al-Walid Ibn Abd Al-Malik, the Mihrab or prayer niche—either flat or concave—was first introduced as Qibla's marker or idiom, to give the illusion of directionality in mosques. When concave, it also served as an architectural acoustic device.

This architectural element is now used excessively in print and other forms of material culture without necessarily building upon its meanings, reducing it to a shape inherently lacking in expression. |

|

Another recurring component is the frame, which surrounds the content of many religious commodities and beyond, a visual tradition adopted from earlier manuscripts.

Qurans decorated with foliate, vegetal and geometric motifs and illuminations are known to have existed as early as the tenth century. These frames served several purposes, occupying the margins of the page like a halo surrounding the sacred words and elevating supreme doctrinal points. Such illustrations were varied to announce the opening and closing words of the holy book and directed the reader to standard divisions of the text. The structure, motifs and colours of these text frames also served as indicators of the manuscript's geographic origin.

Today, the frame does not necessarily fulfil the task of glorifying the content captured inside it, nor does it provide us with leads or specific historical interpretations.

|

|

This brief text proposes to open the inquiry to different forms that may arise if we use reason to free ourselves from the presumed authority of our past.

Could we more effectively reassess the restless lives of images as they migrate from one setting to the next? At what cost does this occur? What are their origins, genealogies and histories? How does that impact their potential to mobilise sentiment? What effect does this have on the level of agency they display or their ability to convey meaning? Images are not necessarily evolving, but how we build on and use them has. Could we pause to closely examine our yesteryear and rediscover its link to the present since this chain of inheritance and its influence is potentially how our identities are formed?

|

About the Author

|

Rasha Dakkak is a Palestinian designer whose work explores the intersections of publishing and teaching design. She is the editor-in-chief and creative director of Bayn Journal, a periodical advocating the importance of shaping a climate that stimulates and supports the discourse on graphic design in the Arab world. Dakkak completed her postgraduate studies in Graphic Design and Iconic Research from the University of Illinois, Chicago, and the Basel School of Design, Switzerland, with work exhibited at venues such as Salone del Mobile in Milan, Amman Design Week, Weltformat Graphic Design Festival in Lucerne, Dubai Design Week, and The National Museum of Riyadh, as well as several professional publications, such as AIGA Eye on Design, Domus Germany, and Wallpaper*. Dakkak lives and works between Abu Dhabi and Amsterdam. |